The Visible Hand: Identifying Adam Smith's Handwriting

Authors: Alison Wiggins and Ana Paula Londe Silva

Published: 5 June 2025

Download PDF1. Caveat lector: marginalia by many different hands

Reader beware: marginalia in Adam Smith’s library books cannot automatically be assumed to be by Adam Smith himself. Smith did write in his books. But he was not responsible for every single mark in the margins and on the flyleaves. Marginalia by earlier owners appears on books that were inherited, gifted, or bought second-hand, and by later readers on books that continued to be used for many years after Smith’s death (as described in the essay on The Marginalia in Adam Smith’s Books by Ana Paula Londe Silva). One of the immediate challenges presented by this wide array of readers’ marks is how to identify annotators and distinguish Smith’s own handwriting?

With this question in mind, this essay has three aims. First, to describe the methods applied within this project for authenticating Smith’s own hand, for the sake of transparency and replicability. Second, to indicate how handwriting identification matters as a piece in the puzzle in investigating Smith and his library. Third, to offer a ‘field guide’ for anyone seeking to spot Smith’s handwriting ‘in the wild’, in archives and in the margins of his books. To these ends, this essay presents samples of Smith’s handwriting to aid recognition of its distinct visual forms and features, to allow users of this digital resource or encountering Smithian material in archives to begin to make their own judgements with more accuracy and precision.

2. Handwriting profiling as a methodology for scribal identification

Handwriting profiling is a well-established methodology for scribal identification. It involves creation of a rigorously compiled profile of a scribe’s handwriting, based on systematic empirical observation, which is subsequently used to find that scribe in other texts by a process of matching hands. It is a method that tends to be associated with medieval and Early Modern palaeography or with modern forensic police work, i.e. the periods before and after Smith was writing (Davis 2007). The assertion, here, is that it is a method also applicable to eighteenth-century handwriting and to Smith himself.

The first step in creating a palaeographic profile is to locate a sample of the scribe in question’s handwriting. Where a suitable sample is not available, handwriting analysis becomes more subjective and tentative, or altogether impossible. Fortunately, in the case of Smith, autograph letters survive from across several decades of his life, authenticated by provenance, style, content, and materiality, which offer a sample that is sizable, precisely datable, and readily accessible to researchers. There are 16 of Smith’s autograph letters accessible through University of Glasgow Archives and Special Collections that since 2024 have been available Open Access as high-resolution colour digital images from The Adam Smith Collection via the University of Glasgow on JSTORE. Therefore, it is now possible to compare side-by-side on screen Smith’s autograph letters with marginalia from across his library books held in different repositories internationally.

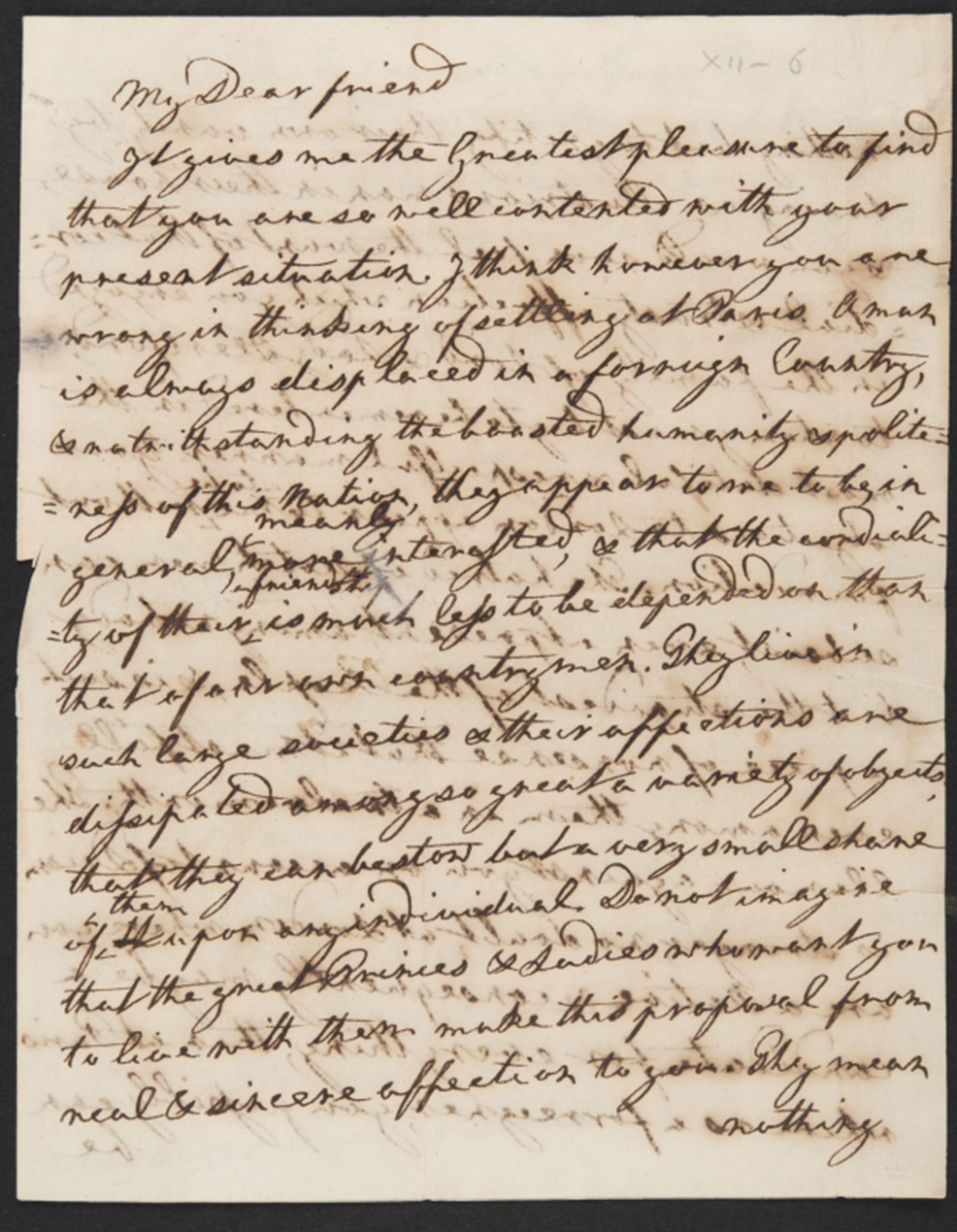

The second step in creating a secure handwriting profile is to comb the selected sample texts using a questionnaire-style survey. The structured dataset generated becomes the basis for comparison and descriptive profiling. Researchers typically create a grid or chart ordered alphabetically and illustrated with close-up images of letter-forms alongside whole-page samples of writing (e.g. Davis 2007, May 2013, Mooney et al 2011, Veitch n.d.). Profiling proceeds on the basis that every hand is unique and an individual writer will exhibit degrees of individuality in the fine details of their handwriting, even through they will have been taught a set of conventions and have a model script in mind. Profiles are designed to capture both the conventional model forms used and the distinctive features of their execution and include as minimum a record of:

- Letter-forms: the morphology of individual graphemes, allographs, and ideographs. A more detailed profile may calculate consistency and variation in the use of allographs, such as their relative frequency or constrained distribution (May 2013). There may be a record of punctuation marks, diacritics, graphs from other scrips, flourishes, and calligraphic features.

- Duct and aspect: the overall style and appearance of the hand, with observations on the pen-strokes, such as the capacity and proclivity to turn the pen, to taper strokes, to use blunt or clubbed ends, the degree of cursivity, fluency, pressure, or shake, the spacing between words and letters, connections between letters, angularity, slope, the proportions of different parts of graphs relative to one another, and the chiaroscuro pattern of light-and-dark on the page (Parkes 1979, 2008).

3. The evolving arc of Adam Smith’s handwriting in his letters, 1741-89

An ideal palaeographic profile would be more than a fixed grid of forms drawn from one sample text. Ideally, a profile would also capture variation and change across an individual’s handwriting, which would include instances where a scribe adapts their hand according to context or text-type, or makes a sudden switch in practice at a particular moment in time, or if their hand evolves gradually over time. This kind of more comprehensive profile requires surveying multiple documents from different periods. Where possible, a handwriting profile will indicate more-or-less stable features of the hand alongside features that tend to vary and change. The advantage of sampling from multiple datable texts is shown in the case of Smith’s autograph letters, which reveal consistent features in the context of the evolving arc of his handwriting over time.

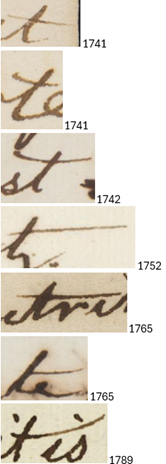

To take as examples the letter-forms <e> and <t>. Smith uses round <e>, never the secretary-form or epsilon allographs of <e> that appear in some contemporary hands (Veitch n.d.). Typically, Smith’s <e> is an upright loop. Although, when he writes more cursively, the loop can become a shallow, squinting eye that resembles a <c>. The tail of the <e> is often extended, especially in the terminal position.

<e> sampled from Smith’s autograph letters:

Smith most frequently uses a form of <t> comprised of two pen-strokes: an ascender and a crossbar. It is notable that Smith’s crossbars on <t> display wide variation and may be long or short, straight or bowed, may evenly extend from either side of the ascender or have a longer extension to the right or to the left, and with different degrees of tapering. Interspersed with this most frequently-used form of <t> are two others: <t> with no crossbar, and <t> with an upstroke extending from the base of the ascender without lifting of the pen, which is most often used the terminal position and is associated with more cursive writing:

<t> with a range of styles of crossbar, sampled from Smith’s autograph letters:

<t> with no crossbar, sampled from Smith’s autograph letters:

<t> with upstroke extending from the base of the ascender with no pen-lift, sampled from Smith’s autograph letters:

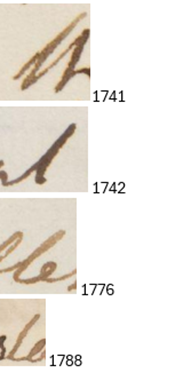

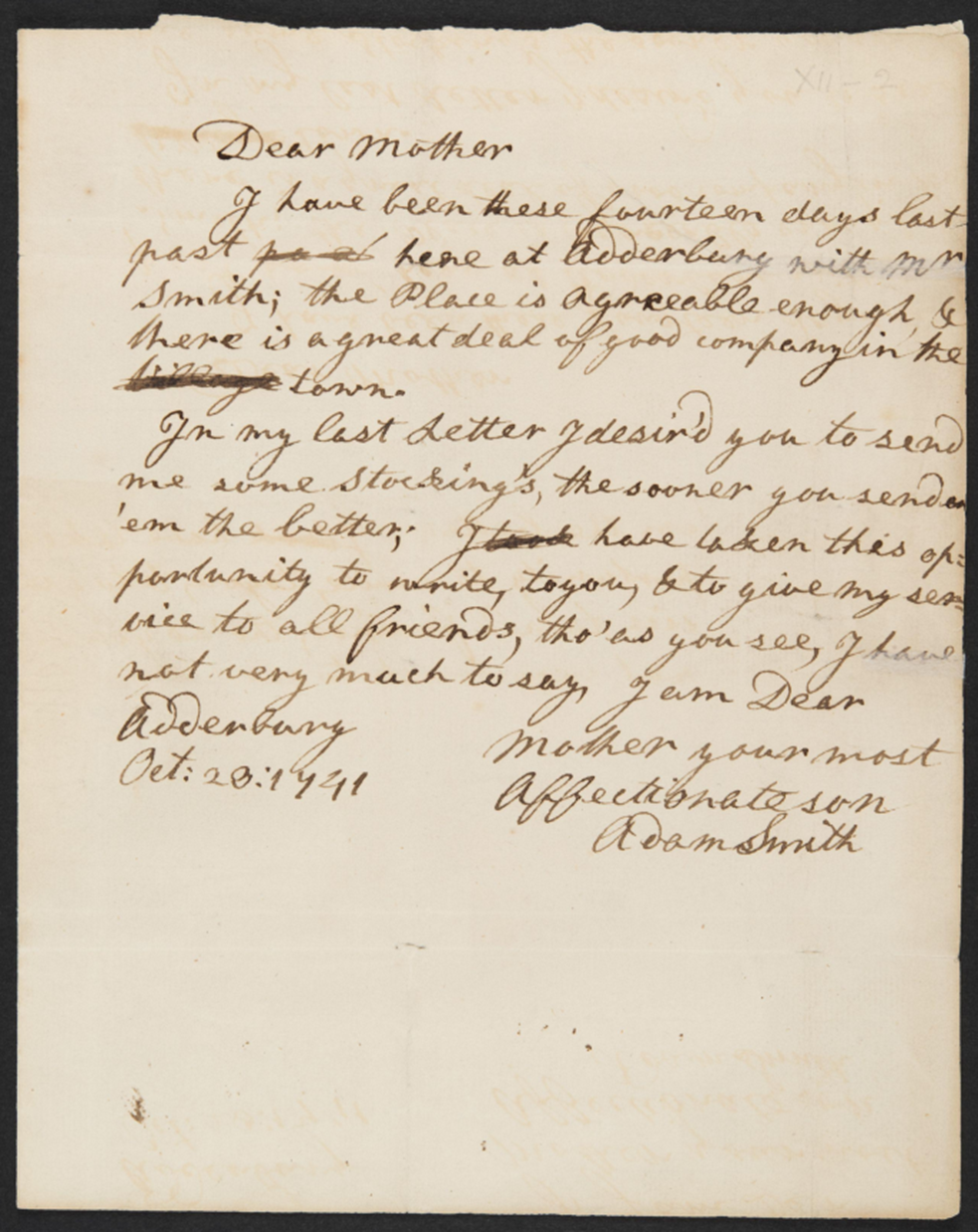

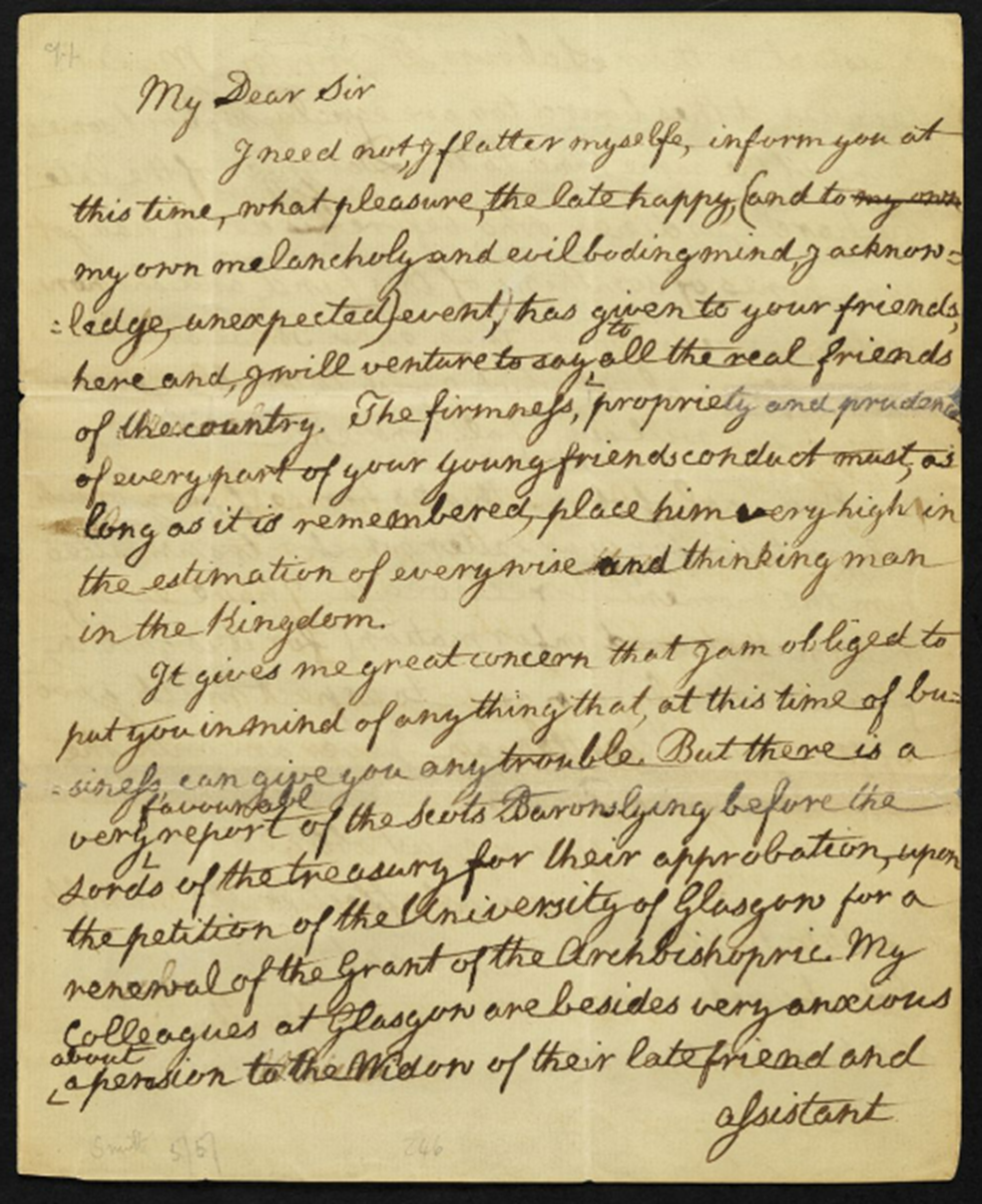

To consider these forms in their wider context, below are three sample letters written in Smith’s own hand at approximately quarter-century intervals:

From 23 October 1741 to his mother:

September 1765 to David Hume:

From 25 March 1789 to Henry Dundas:

These three autograph letters display Smith’s characteristic forms of <e> and <t>, described above, viz:

- round <e> is always used, never secretary or epsilon <e>. In more cursive writing, the eye of the loop is tighter and sometimes squinted so the <e> resembles <c> (1765 the first <e> of ‘however’ l. 4, ‘great’ l. 13), this squinted form being rarer in his less fluently-penned late letters that prefer rounded loops (1789 ‘late’ l. 3, ‘gives’ l. 12).

- <t> is most frequently written with a crossbar and the styles of crossbar show variation in length, position, curve, taper, and pressure. In addition to this form, all three of these autograph letters by Smith feature some forms of <t> with no crossbar (1741 ‘there’ l. 5, ‘taken’ l. 9, and in the subscription ‘Mother’; 1765 ‘dissipated’ l. 13; 1789 ‘the’ l. 7, ‘their’ l. 16). In the more cursively written letter from 1765, Smith regularly used the form of <t> with an attached upstroke with no pen-lift, typically where <t> is in the terminal position (1765 ‘it’ l. 2, ‘present’ l. 4, ‘at’ l. 5, ‘great’ l. 13).

These examples of <e> and <t>, then, illustrate Smith’s characteristic use of two letter-forms across his life. His use is conventional and follows a model script, but the particular combination of variations and the fine features of execution give a framework of expectations about Smith’s hand. A comprehensive handwriting profile will record every grapheme and therefore provide a fuller and more detailed framework of expectations.

These three autograph letters further illustrate distinctive features of duct and aspect. Notable is the forward-leaning direction of the handwriting at 5–10 degrees, the mix of hooked and straight approach strokes, and use of exaggerated tapering strokes especially but not exclusively to finish letters in the terminal position. Also notable is that Smith’s 1789 letter is markedly less fluent. This decline in fluency is part of a wider pattern whereby during the 1780s Smith’s autograph writing became increasingly laboured and displays heavier pen pressure, less fluidity, and more angularity, indicative of gradually reduced manual dexterity or eyesight. By 1788-89 we see a shake appear. When a person suffers physical decline it will be reflected in their writing and is often associated with later life or disability. These features cannot be easily controlled and can be progressive, so may contribute to identifying an individual or dating their writing. Smith’s biographer and editor describes his handwriting as ‘slow’, ‘laborious’, and ‘like that of a child’, whereas systematic profiling indicates this only to be true for the end of Smith’s life and to be a development in Smith’s hand (Ross 2010: 250; discussed by Phillipson et al 2018: 362-63). In summary, we can observe in Smith’s hand a repertoire of graphemes and allographs that remain stable over time and that exhibit distinct fine features and areas of variation. The main change over time occurred later in life as his had became more laboured with age and developed a shake in his final years.

4. Identifying Adam Smith’s handwriting in his content lists

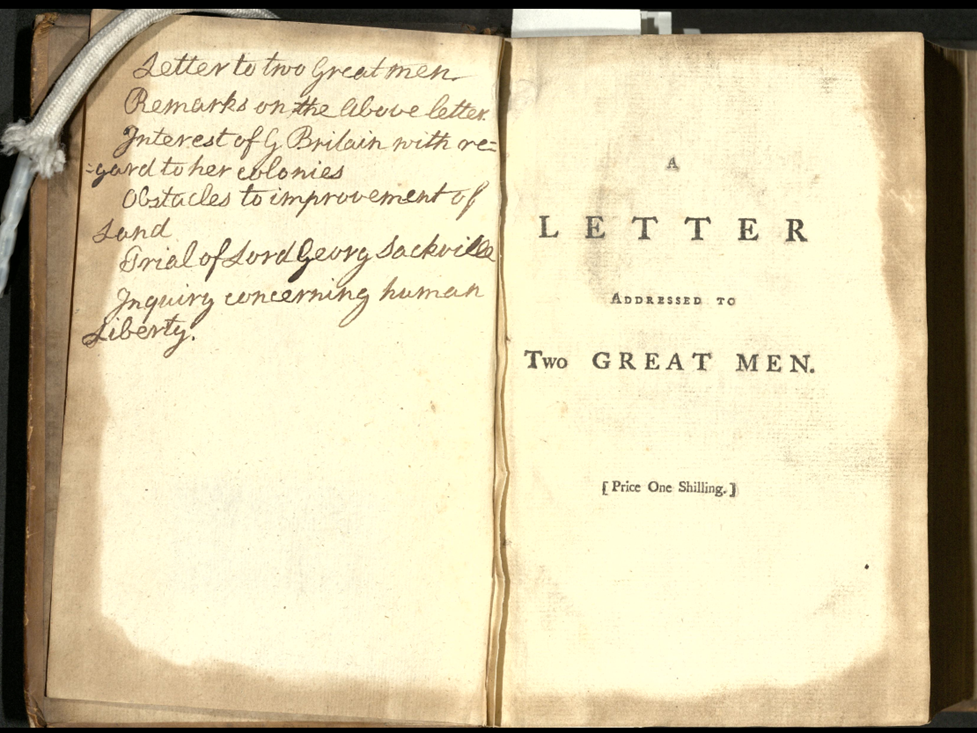

A highlight from the marginalia from Smith’s library are the contents lists added to the flyleaves of bound books of pamphlets. These handwritten contents lists were identified by Londe Silva in 2024, who compelling argues that they are by Smith himself, that they provide fresh insights into his working methods, and that they offer a unique and valuable window into his evolving topical, intellectual, and political interests (forthcoming 2026). Londe Silva asserts Smith as author and there is no doubt this is a valid attribution. These contents lists can be securely authenticated as penned by Smith himself in his own hand through the process of comparing hands or (to use May’s phrase) ‘matching hands’. That is, the contents lists can be authenticated by matching their features with the profiled dataset of Smith’s handwriting compiled from his autograph letters. The contents lists are of sufficient length and size to provide a substantial sample, suitable for confident identification. To give an example. The Edinburgh University Library bound ‘Volume of Miscellanies’ features a handwritten contents list:

This contents list is not signed by Smith (nor would we expect it to be), but it can be authenticated as penned in his hand. The overall duct and aspect is distinctive of Smith’s handwriting in respect of:

- the characteristic degree of the forward-leaning angle

- the relative height of minimis to the height of ascenders and descenders

- the proportionality of letters, such as the height and width of bowl, body, and arch relative to ascenders and descenders

- the degree and style of tapering on the ends of the tails and crossbars of letters

- the spacing between words, letters, and lines that results in an overall pattern on the page.

Further, the repertoire of letters-forms is consistent with the profile of Smith’s handwriting:

- <a> is an open bowl formed with an initial loop (‘Great’ l. 1, ‘Land’ l. 6, ‘Trial’ l. 7, ‘human’ l. 8).

- <c> is formed with a looped top (‘colonies’ l. 4, ‘Sackville’ l. 7, ‘concerning’ both letters l. 9).

- <d> with forward-leaning ascender and unclosed bowl (‘re=gard’ ll. 3-4, ‘Lord’ l. 7) and in some cases the body is more than half the height of the ascender (‘Land’ l. 6). While Smith uses both secretary and italic forms of <d> it is not surprising that only one of these appears here.

- <e> is round-form written as a loop, at times upright and rounded (‘men’ l. 1), at other times narrow and tilted like a squinting eye, sometimes the loop so compressed that the <e> has a c-like appearance (‘Great’ l. 1).

- <g> with an open bowl and a looped descender, where the tail may either barely close the loop (‘concerning’ l. 8) or may pass through it (‘Georg’ l. 7).

- <m> where the foot of the second arch is sometimes higher that the foot of the first (first <m> of ‘improvement’ l. 5).

- <m> and <n> that terminate with an exaggerated upward tick or tail, tapered, that may extend to pass through the next letters or next word (‘men’ l. 1, ‘Remarks’ l. 2, ‘on’ l. 2).

- <t> with a range of styles of crossbar that include: a shorter blunt crossbar of equal length either side of the ascender (‘letter’ l.2, first <t> of ‘Interest’ l. 3), a longer tapering crossbar where the right-hand side of the cross-bar extends into the next letters or word (‘to’ l. 1, ‘Great’ l. 1, ‘improvement’ l. 5), alongside the form of <t> with no crossbar (‘Britain’ l. 3).

These features in combination with one another, taking into account their frequency and distribution, and in the context of the features of duct and aspect, align with expectations of Smith’s hand. The quality of the sample and clarity of the match allow for confident attribution of this contents list to Smith. Further, the same process of authentication by matching with the reference profile confirms that Smith penned the contents lists handwritten in 10 more bound volumes: ‘Tracts on Grain Trade’, ‘Consideration on Money, Bullion, &c, &c, &c', ‘Price on Civil Liberty &c.’, ‘Dupleix’, ‘State of the nation 1760s-70s’, ‘Tucker’s tracts’, ‘Public Affairs’, ‘Political Pamphlets’, ‘Pamphlets’, and ‘Recherches sur la population’ (another volume of ‘Pamphlets’ and the volume titled ‘Charity’ have similar contents lists but these are written in other hands, perhaps by librarians or later owners). The variations in style between these contents lists suggests they were added by Smith at different points in time, i.e. after the topical pamphlets were assembled, rather than all together at a later point. They give us Smith at work, pen in hand, in his library.

5. Next steps

The results of handwriting analysis exist on a spectrum. At one end are the contents lists confirmed to be in Smith’s own hand, where the results of analysis allow for very confident matching of annotations to a known scribe. At the other end are numerous examples of underlining and marginal place-markers (ticks, crosses, dots, and dashes) that are highly resistant to handwriting analysis. Underlining or place-markers alone, while they may tell us about a reader’s interests, are unsuitable for palaeographical profiling. Underlining, ticks, crosses, dots, and dashes are especially numerous in the the portion of Smith’s library that later came to be on the open shelves of Edinburgh University Library, so appear to tell a story about the use of Smith’s books by generations of students, even if we do not know their individual names or biographies.

In between these two poles, somewhere mid-scale in degrees of certainty, are marginal notes that give an imperfect sample because they are very short, or are varied in their alphabets and scripts, or written into compressed spaces, all of which factors make it more difficult to match these scribal hands against a reference profile. Conclusions come down to a balance of probabilities and judgement over the likelihood of an attribution that is partly based on experience and relies on the quality of the dataset. For these reasons, palaeographers and forensic document examiners tend to be cautious in their identifications and to answer yes/no questions in the form of reports that assess the complexity of the evidence and weigh the possibilities.

Within this digital resource, we do not have a binary yes/no field to handle identificatons or attributions to Smith. Rather we are in the process of building a bank of notes and statements for decoding the marginalia. This essay seeks to encourage interest in the library and to be a resource for reseachers in their analyses of Smith’s own writings and annotations. The intention, next, is to publish a more comprehensive profile and dataset for Smith, along with further observations on highlights from research into his library, in part in response to the most thorough published consideration of the marginalia to date, which calls for additional focus on the palaeography (Phillipson et al 2018: 373-75). In the meantime, this essay offers an insight into the methods used for the project and shares a preliminary dataset for Smith’s hand.

Resources

The Adam Smith Collection, University of Glasgow and JSTORE

https://www.jstor.org/site/university-of-glasgow/the-adam-smith-collection/

Preliminary dataset of Smith’s letter-forms, shared 5 June 2025, downloadable spreadsheet

References

Davis, Tom, ‘The Practice of Handwriting Identification’, The Library, 7th Series, 8.3 (2007): 252-76

Londe Silva, Ana Paula, ‘Adam Smith’s Engagement With the Public Debate: Lessons From His Library’, in New Voices on Adam Smith’s Philosophy, Politics and Economics: Essays Marking the 250th Anniversary of the Wealth of Nations, ed. by Criag Smith, Ana Paula Londe Silva, and Leo Steeds (Scottish Universities Press, forthcoming 2026)

May, Steven W., ‘Matching Hands: The Search for the Scribe of the “Stanhope” Manuscript’, Huntington Library Quarterly, 76.3 (2013): 345-375

Mooney, Linne, Simon Horobin, and Estelle Stubbs, Late Medieval English Scribes, Universities of York and Oxford and The Digital Humanities Institute at the University of Sheffield (2011) https://www.medievalscribes.com

Mossner, Ernest Campbell, and Ian Simpson Ross eds, The Glasgow Edition of the Works of Adam Smith, The Correspondence of Adam Smith, second edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1987)

Parkes, M. B., Their Hands Before Our Eyes: A Closer Look at Scribes, The Lyell Lectures Delivered in the University of Oxford 1999 (Routledge, 2008)

_____ English Cursive Book Hands 1250-1500 (Ashgate, 1979)

Phillipson, Nicholas, Shinji Nohara, and Craig Smith, ‘Adam Smith’s Library: Recent Work on his Books and Marginalia’, The Adam Smith Review, 11 (2018): 355-77

Ross, Ian Simpson, The Life of Adam Smith, second edition (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010)

Veitch, Kenneth, Scottish Handwriting in the Eighteenth and Nineteenth Centuries: A Concise Guide (The European Ethnological Research Centre, University of Edinburgh; no date) https://www.regionalethnologyscotland.llc.ed.ac.uk/sites/default/files/scottish_handwriting_a_concise_guide.pdf (accessed May 2025)