Adam Smith's book collecting

Author: Craig Smith

Published: September 2024

Download PDF‘a beau in nothing but my books’

Adam Smith loved reading and collecting books. He once remarked to the printer William Smellie, who was admiring his library during a visit to Smith’s home, that ‘I am a beau in nothing but my books,’ a self-deprecating reference to the beauty of the books in his library when compared to his other vanities of appearance. Smith grew up in a house that was well-stocked with books for an eighteenth-century home. His father, who died before he was born, left a collection of books to the family. We have a list of these books from the winding up of his estate. Many of them were religious texts doubtless favourites of Smith’s devout mother Margaret Douglas Smith, but there were also books in French (perhaps acquired during Smith senior’s trips to France) and popular literature like The Spectator.

Books for School at Kirkcaldy

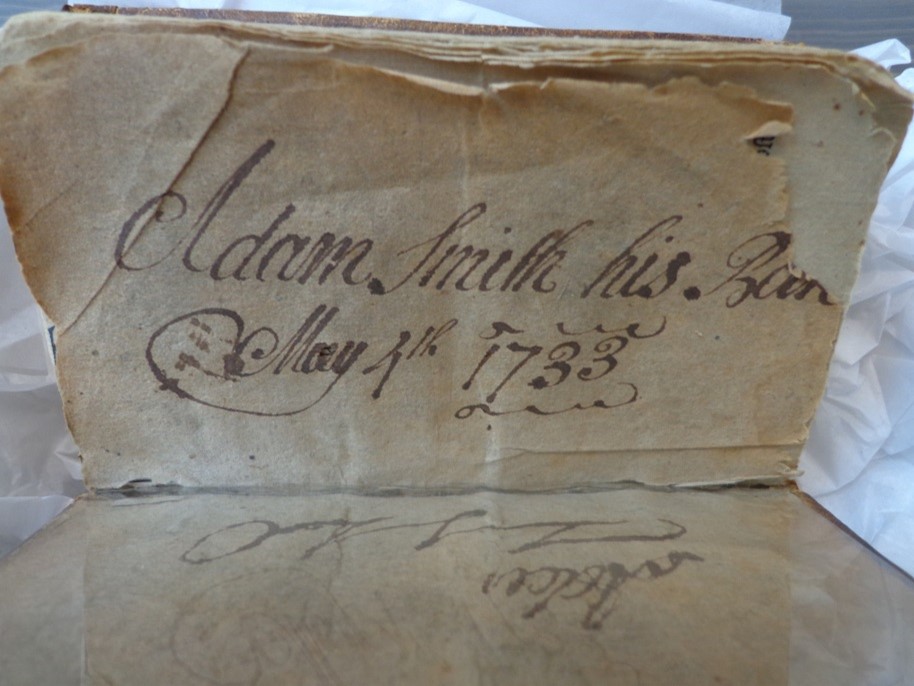

It is impossible to trace when Smith first started to collect books, but one example of early book buying is a book held by Kirkcaldy Museum: Smith’s copy of Eutropii Historiae Romanae breviarium in usum scholarum. This was a standard school text of the time and Smith would have been required to complete classroom exercises from it in the Burgh School at Kirkcaldy. The book was published in London in 1725, so we know that it was purchased for Smith (rather than for his father, also called Adam Smith) because it post-dates his father’s death. The book has examples of Smith practising his signature in the inside of the cover, complete with the date 1733. Nine year old Adam was already keen to mark books as his own. Something he continued to do later with his own elegant bookplate.

Books as Student and Professor at the University of Glasgow

W. R. Scott suggests that as a young man Smith likely had little in the way of funds to build his own library and instead used Glasgow University Library while he was a student (1737-1740). It also seems that he spent much of his time when he was at Oxford in private study in the Balliol College (1740-1746) and University libraries, and at the library at nearby Adderbury, where a relative was estate manager for the Duke of Argyll. This practice continued during Smith’s time as a professor at Glasgow where we have records of his borrowing and of the books that he signed out for students. Smith also served as Quaestor and was responsible for purchasing books for the University Library. These famously included the Encyclopédie, with its illustration of a pin factory, which remains in the University collections to this day. We also have a 1753 letter from his friend David Hume, then Keeper of the Library of the Faculty of Advocates in Edinburgh offering Smith use of the library when he was in the city.

Book Collecting in London and Paris

Scott surmises that it was only later in life that Smith began to build his own library in earnest. One piece of evidence for this is that many of the books that we know that Smith ordered for the Glasgow University Library were titles that he later went on to purchase for himself. We also have evidence of Smith acquiring editions of books that he cites in earlier publications, for example he has both a 1753 edition of Rousseau’s Ouevres and a 1760 edition of the Oeuvres Diverses the latter of which includes the Discourses and post-dates his discussion of the Discourse on the Origin of Inequality in the Letter to the Edinburgh Review of 1756.

That Smith began to consolidate his library after his time in Glasgow seems to be supported by a letter he sends to the publisher Thomas Cadell in 1767 arranging for books to be sent to Edinburgh in preparation for his return to Scotland. These books likely having been purchased in France, or in the period spent in London on his return with the Duke of Buccleuch. This leads Hiroshi Mizuta to trace the beginnings of Smith’s library to his time in France with the Duke in 1764-6. There is also another letter to David Hume sent from London in 1775 which discusses sending books north that had been purchased while in the city taking the Wealth of Nations through to press. This suggests that Smith took advantage of travel to gain access to booksellers, a point confirmed in the discussion of book buying in Paris with Hume in a letter sent to Smith in August 1766.

Beautiful Books, Rare Books, and Presentation Copies

This general view is supported by the fact that many of the books in Smith’s Library have publication dates from the 1770s and 1780s. A number of these, such as his presentation copy of Gibbon and the complete works of Voltaire, are very finely bound presentation editions which no doubt prompted William Smellie’s admiring comments on the library. Several, such as the copy of the 1758 edition of Hume’s Essays and Treatises on Several Subjects and Robert Wallace’s Thoughts on the Origins of Feudal Tenures of 1783, are marked as gifts from the author.

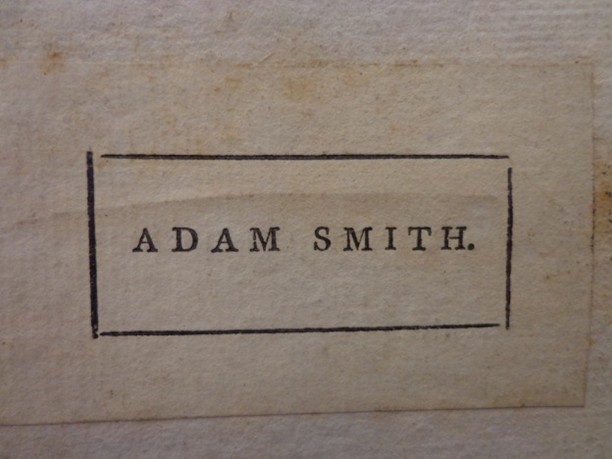

Smith’s taste for beautiful books saw him build an impressive personal collection. The collection includes books published across Europe and ranges from first editions to multi-volume collected works, by way of pamphlets. There are books in Latin, Greek, French, German, and Italian. They are almost always tastefully bound, and many have beautifully preserved marbled flypapers. That Smith sought out particular volumes is clear in his purchase of a 1543 first edition of Copernicus’ De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium (The Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres). This is an extremely rare and very beautiful book and one that Smith obviously took some effort to acquire. Almost all of these books are marked with the now famous bookplate. Plain, yet remarkably stylish, appears broadly the same across Smith’s library.

Their near ubiquity might lead us to believe that these bookplate labels were added to his books late in life, but there is reason to doubt this. Examination of the bookplates themselves suggests small differences between them which may relate to different batches acquired at different times, though it is unclear if these differences are consistent enough to assist in dating Smith’s acquisitions, it does suggest that they were not all applied at the one time.

Second-Hand Copies and Pamphlets

While we can assume that Smith’s purchases increased with his income, it seems equally likely that his interest in books existed throughout his life and that he bought when he could and what he could afford. We should expect that a portion of Smith’s library was bought second hand. We find evidence of Smith’s purchase of pre-owned books in the signatures and bookplates of previous owners being apparent in several volumes. Some of these bear the bookplates of Scottish owners suggesting that Smith acquired them in Edinburgh or Glasgow, but others are from further afield and reflect international commerce in books.

Another indication of Smith’s enthusiasm for books is his practice of creating bound volumes to preserve pamphlets. These often come with handwritten contents lists and are sometimes dedicated to a single source or topic. Several of them are bound collections of parliamentary papers from Britain and France, others include collections of pamphlets on a single issue. An example is the bound volume of papers on the Calas affair that are likely a product of Smith’s time in Toulouse with the Duke of Buccleuch.

A Polymath’s Library at Panmure House

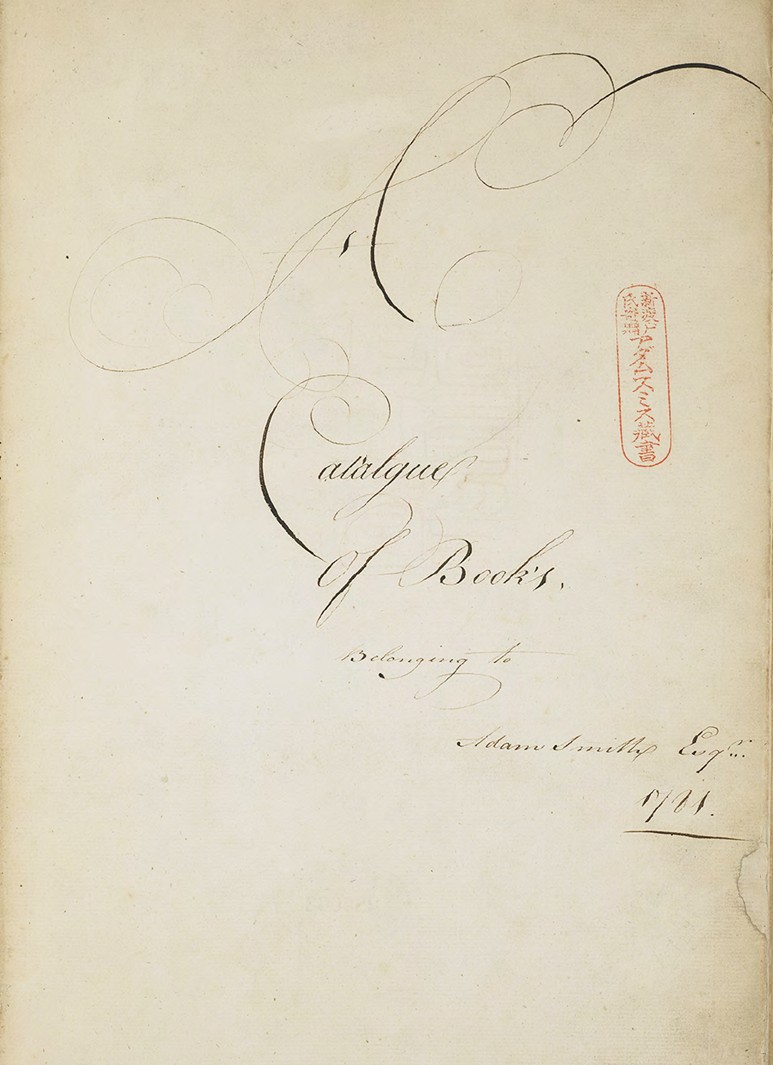

So, what did Adam Smith collect? The answer seems to be everything. Smith’s interests were polymathic, and he had extensive collections in Ancient Greek and Latin, in French literature, in political economy, on music and poetry, on the natural sciences and mathematics, and on history and law. He was obviously very proud of his collection. When he moved the books into his final home, Panmure House in Edinburgh, he had them shelved around a large room which served as his study. Smith had his secretary create a catalogue of his Library in 1781. The catalogue lists his holdings at that point and indicates where they are shelved.

Adam Smith was obviously a man who read widely and loved books. In common with his fellow literati of the Scottish Enlightenment, he was eager to read and discuss the latest works of science, history, philosophy, and literature. It seems likely that his library became a resource for the household, such as his young heir David Douglas who lived with Smith as a schoolboy and student and took advantage of the extensive collection. We also have evidence of Smith giving books from his collection as gifts to friends including the advocate Allan Maconochie.

As Smith became wealthy and famous he was able to assemble a fine collection of books through purchases and gifts. His comment that he was a beau in nothing but his books, may have been a witticism in one sense, but it seems that it spoke to a wider truth. Adam Smith liked beautiful books, and when he acquired the means to do so he filled his home with them and enjoyed his retirement reading them.

References

Mizuta, Hiroshi Adam Smith’s Library A Catalogue

Scott, W. R. Adam Smith as Student and Professor

Diderot et al Encyclopédie

Smith, Adam The Correspondence of Adam Smith (ed.) I.S. Ross

Further Reading on Adam Smith’s book collecting

Ross, Ian Simpson The Life of Adam Smith

Phillipson, Nicholas Adam Smith an enlightened life

Sher, Richard B. The Enlightenment and the Book Scottish Authors and their Publishers in Eighteenth-Century Britain, Ireland, and America